Leaked video claims tech companies staffing up with ex-cops and becoming increasingly responsive to wiretap demands

PenLink representative Scott Tuma explained details on Wednesday of increasing cooperation from Google, Facebook, Snapchat et al. on law enforcement wiretaps for both messages and location data.

I almost feel bad writing this story, as this is the second time I have reported on recordings of Scott Tuma, the Director of Internet Solutions at wiretapping contractor PenLink. The first time was February of last year, when I attended his session at the National Sheriffs’ Association, where he discussed how his company helps police conduct search warrants for Google search histories and GPS location data, as well as how warrants for Apple iCloud backups often provide “phenomenal” access to conversations conducted on end-to-end encrypted messaging applications such as WhatsApp. Perhaps the most bizarre segment was a sheriff in the audience lamenting having flown a drone over an empty field as a result of inaccurate location data obtained through the Sirius XM radio subscription in their target’s truck.

(At the same conference I accidentally caught police on tape pitching Taser manufacturer Axon on how to bribe then head of Rhode Island State Police, Jimmy Manni, through free trips to a hunting farm run by former Patriots offensive tackle Matt Light; the governor announced Manni’s retirement the next month. Separately, another former police officer was caught on video joking about bikinis clogging the quasi-Disney-related police surveillance robot he was pitching — as well as how police would likely roll them into the women’s locker rooms.)

But in a webinar hosted Wednesday by police training company Lexipol, Tuma claimed that, over the last two years, tech companies have been staffing up their security departments with ex-police and are becoming increasingly responsive to wiretap requests:

“Is it getting easier to work with these companies? I will tell you, in most cases, yes it is. They are bringing in and expanding their security groups to bring in ex law enforcement. Law enforcement that have experience in working these types of cases. The passion is there for these individuals once they move from the law enforcement world to the private sector.”

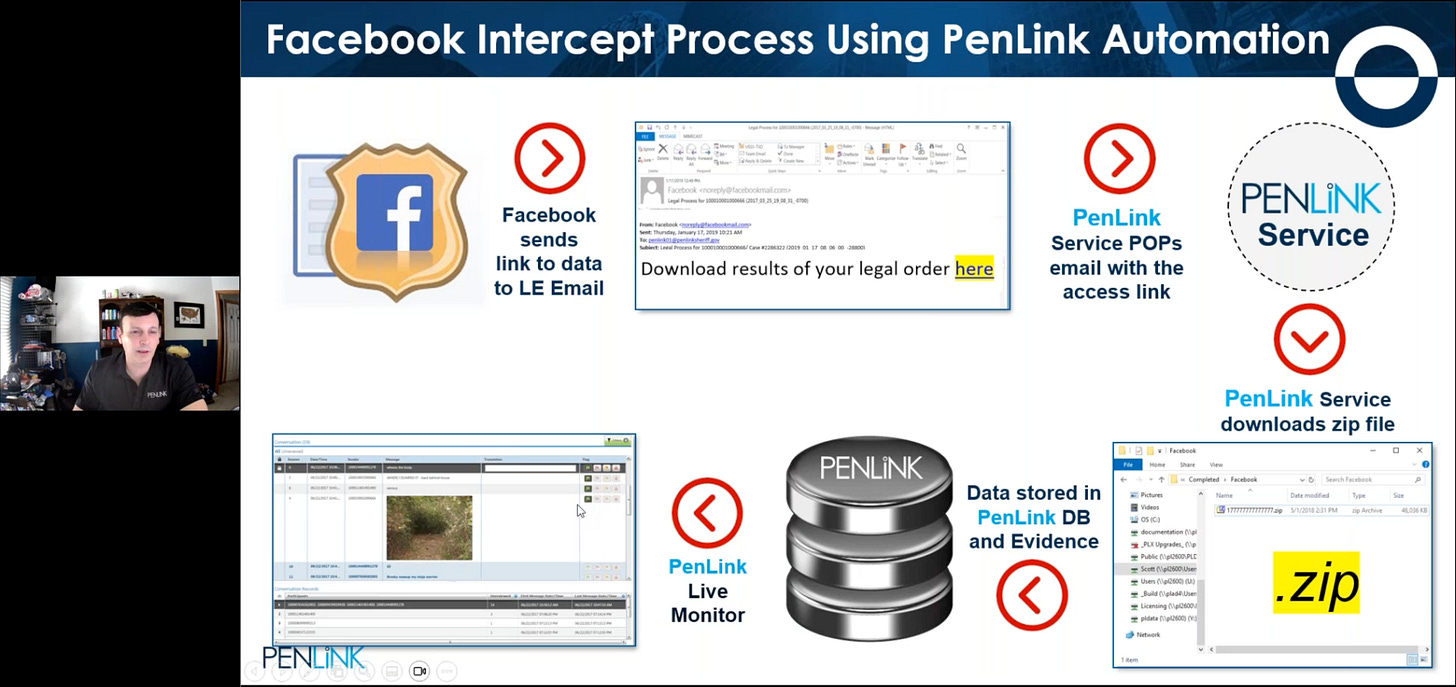

In the case of Snapchat, Tuma asserted that the company has increased its response speed for live content warrants — or “Title III” cases — from once a week to once an hour. Though tech giants like Facebook and Google email police updates every fifteen minutes.

(The FBI advertised Tuma’s participation in a webinar on “how to request and analyze” Apple iCloud backups at 1pm ET the same day. And today Forbes reported how the FBI can dig up “scrambled” versions of nominally deleted WhatsApp messages using Cellebrite’s forensics software — which PenLink also advertises integration with.)

Tuma’s presentation laid out a typical surveillance workflow when starting with just a target’s phone number: by demanding the histories of Internet Protocol (IP) addresses the phone communicated with through the telecommunications provider — Tuma frequently names Verizon — police can determine which tech companies to subpoena for login histories or submit search warrants to for live content and cellphone location data intercepts.

(While Tuma did not explicitly name National Security Agency whistleblower Edward Snowden, he lamented that, until roughly ten years ago when encryption started to become the standard, PenLink would simply demand a complete copy of all packets transmitted between phones and carriers such as Verizon and then reconstruct the entirety of the traffic to each application. But now, unless police get lucky through an Apple iCloud backup or get physical access to the phone for forensics, they need separate search warrants for each social media account.)

Despite Tuma repeatedly mentioning search warrants for Meta products including Facebook Messenger, WhatsApp, and Instagram — including their 15 minute update cycle for “live” Title III warrants — there was no discussion as to whether WhatsApp’s end-to-end encryption prevents access to message content. Beyond Tuma’s previous description of potential access to WhatsApp messages through iCloud backups, Rolling Stone reported the conviction of Treasury whistleblower Natalie Edwards having been supported by the FBI’s analysis of the metadata from her WhatsApp conversations with a BuzzFeed reporter.

(By contrast, it is currently assumed that U.S. police and intelligence agencies cannot acquire even metadata for conversations conducted on the messaging application Signal through search warrants, though all bets are off if an intelligence agency has hacked into or seized your phone.)

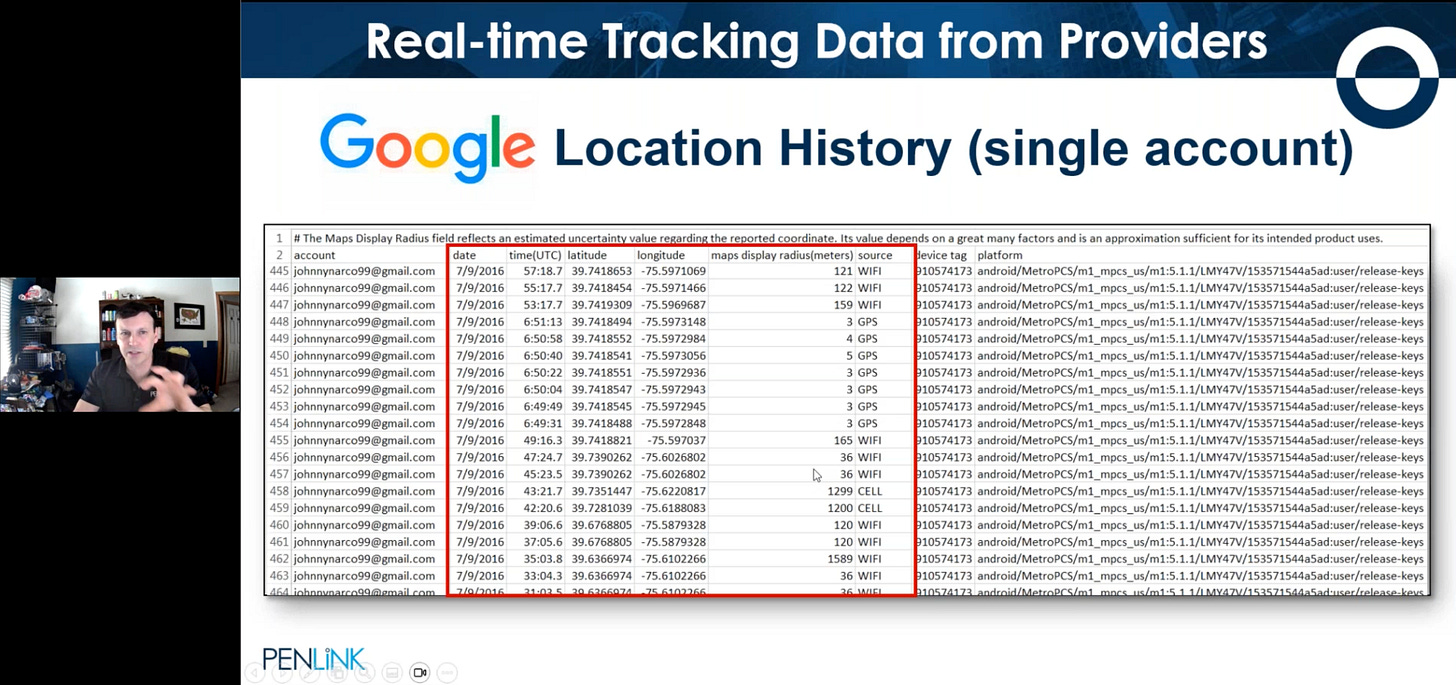

Two of the most telling slides from Tuma’s Wednesday presentation related to what information PenLink recommends that police demand from Google — including Google Search histories, cellphone location histories, Google Maps search histories, and all Google Docs created by the target. Tuma also asserted that, while Google and Snapchat annotate each cellphone location datapoint with its estimated spatial accuracy — say, 3 to 5 meters for GPS data, 30+ meters for measurements using nearby WiFi, and 1+ kilometer for cellphone tower pings — to the best of his knowledge, Facebook does not provide accuracy estimates.

In a nutshell, Tuma’s pitch was to simplify the labor-intensive process of manually monitoring the emails which come in every 15 minutes for a Title III search warrant by having PenLink’s PLX software automatically monitor for new emails and incorporate the linked data. (PLX is an acronym for the three tools it combined: the phone-focused tool PenLink8, the collection platform LINCOLN, and the internet-centric tool Xnet.)

Perhaps the most jarring aspect of Tuma’s talk was the contrast between his frequent allusion to murder investigations versus the closing slide centering on wiretapping a small-time marijuana provider. Said advertisement placed the banner text “Your Life Lives Here…So Does Theirs” next to a text message exchange ostensibly demonstrating the sale of a small amount of “Super Lemon Haze”-branded pot to a client. Despite Rolling Stone having reported last month that only six out of fifty U.S. states do not yet have a program for legal THC, the full powers of police wiretaps are being advertised for the persecution of what is increasingly simply the small business equivalent of a legal, multi-billion dollar industry.

(In early 2018, the author attended an official event in a Google office in Toronto, Canada where former Google executive Alan Gertner pitched his new Starbucks-for-weed company, Tokyo Smoke, to an office full of employees — many of whom were investors in weed stocks. Yet Google remains a central component of police surveillance of petty marijuana sales even five years later.)

In the first of three questions at the end of Tuma’s talk, an ostensible member of the U.S. National Guard Counterdrug Program (NG CD) asked how the 15-minute delays from social media search warrants could be used as a technicality to circumvent a restriction against NG CD participation in Title III intercept programs. While the NG CD Program officially began in 1989, its roots were in the Hawaii National Guard’s 1977 usage of military helicopters for the destruction of marijuana fields, and the program has since allowed the U.S. military to work with “more than 300 federal, state, local, tribal and territorial law enforcement agencies across all 54 states and territories.”

After emphasizing that he is not an attorney, Mr. Tuma responded to the Title III circumvention question by stating “that would be kind of a creative way if you don’t have maybe intercept capabilities to maybe ask for it historically. That could be an advantage for you. And so I wish you luck, and, if you can, let me know if that works for you.”

Mr. Tuma did not respond to a request for comment by phone.