[Editorial] In defense of critical citations

The blanket treatment of all article references as endorsements penalizes primary source evidence collection and discourages forensic analysis.

“Elon Musk’s Grokipedia cites a neo-Nazi website 42 times, researchers say,” proclaimed an NBC News headline on Thursday. The 42 references can be readily documented across 15 pages relating to white nationalism — rendering the “researchers say” qualification superfluous — but the article’s presumption of citations as endorsement is worthy of dissection.

This article’s discussion of NBC’s reporting should not be mistaken for an endorsement, for example.

Investigative journalist Seymour Hersh was similarly not endorsing mass murder when he extensively cited former U.S. secretary of state Henry Kissinger’s memoirs in his 1983 books on the now-deceased war criminal, “The Price of Power.” One New York Times book review went so far as to label the book “the Kissinger antimemoirs.”

Any practicing investigative journalist understands that, when individuals speak at length, they can diverge from talking points into confessions of controversial activities, for reasons ranging from contrition to pride. The principle holds not just for phone calls and alcohol-soaked dinners, but for video interviews, books, and online writing. Effective investigative journalism can often take the form of wading through tens of hours of pablum in order to mine a few moments of candor.

But there is of course an ocean in the middle of endorsement and refutation, where journalists are supposed to spend a significant amount of their energy, and which one might refer to simply as ‘evidence collection.’ And the lines can blur: the default template of a journalist quoting individuals on ‘both sides’ of a controversial subject can just as well be noncommitment as allowing a side to verbally hang itself, with the distinction sometimes being in the eye of the beholder.

The danger of citation counting is that, by collapsing the spectrum of citation styles into an assumption of endorsement, authors are discouraged from using more damning, primary-source evidence.

The apparent sin of the centi-billionaire Elon Musk’s artificial intelligence-powered, and at least partially ideologically motivated competitor to Wikipedia — known as Grokipedia — was for 15 of its articles relating to white supremacy to include a total of 42 citations to discussions on the white nationalist forum hosted at stormfront.org. (Of these 42 citations, one is repeated twice, and another is a transcript of Stormfront founder Stephen Donald Black’s 1998 interview, alongside first-amendment lawyer and Clearview AI advisor Floyd Abrams, with Ted Koppel of ABC News.)

Three days prior to publication of NBC’s critique, The Guardian published a compelling analysis of Grokipedia’s lukewarm portrayal of the white nationalist Jared Taylor, focusing on the content of a particular article rather than its metadata. (The website of Taylor’s media outlet, American Renaissance, was the source of 33 out of 94 citations in his Grokipedia article.)

Taylor’s most infamous statement, generally ambiguously sourced to his critical profile by the Southern Poverty Law Center, was that “Blacks and whites are different. When blacks are left entirely to their own devices, Western Civilization — any kind of civilization — disappears.” “And in a crisis, it disappears overnight,” Taylor continued, in the closing statement to his cover article in American Renaissance’s October 2005 magazine, “Africa in Our Midst,” which was published in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina and is still available on the organization’s website.

I cannot speak for the reader, but I am far more inclined to confidently label Taylor a “white supremacist” after directly reading the original article, which American Renaissance continues to host. Arguably, a journalist should be required to engage in such a form of verification, rather than simply using an argument-from-authority citation of a watchdog organization. To obscure the citation is to make verification more difficult.

Out of Grokipedia’s 42 references to Stormfront, NBC’s article focused on the seven originating from an article on the late neo-Nazi William Luther Pierce’s publication National Vanguard and another six from an overview of actor Edward Norton’s portrayal of an American neo-Nazi in the 1998 movie “American History X”:

In an article about a Virginia-based white nationalist publication, Grokipedia cites and links to Stormfront seven times, with the links appearing at the bottom of the article under “references.” A Wikipedia article with the same title cites mainstream sources, such as Newsweek magazine. The Grokipedia version also uses euphemisms such as “advancement of peoples of European descent” in place of labels such as “white nationalist” preferred by Wikipedia editors, and the Grokipedia version is about 15 times longer than the Wikipedia article.

The Grokipedia article for the 1998 film “American History X” cites and links to Stormfront six times, summarizing how people on Stormfront’s discussion forum view the film. The Wikipedia entry for the film does not cite Stormfront, instead relying on movie websites and news publications. (In the film, Edward Norton plays an American neo-Nazi, a role that earned him an Academy Award nomination.)

Apart from the baffling implication that there is something nefarious about expending a multiple of the roughly 350 words which Wikipedia alotted to National Vanguard, Grokipedia is criticized for citing the discussions on the white nationalist forum Stormfront directly rather than “mainstream sources, such as Newsweek magazine.”

The seven Stormfront references in the Grokipedia National Vanguard article are contained with a three paragraph subsection, entitled “Perspectives from Nationalist Movements.” The first of these three paragraphs opens with the phrase “Within white nationalist communities,” despite NBC’s misleading claim that, “The Grokipedia version also uses euphemisms such as ‘advancement of peoples of European descent’ in place of labels such as ‘white nationalist’ preferred by Wikipedia editors.’”

The phrase “advancement of peoples of European descent” does not even occur in the Grokipedia section citing Stormfront — which, again, repeatedly uses the phrases “white nationalist” and the shorthand “nationalist” — and only appears once, in the article’s top-level summary, next to direct citations of the subject of the article.

Five of the National Vanguard article’s seven Stormfront references are documentation of rivalries between white nationalist groups and internal reactions to Pierce-successor Kevin Alfred Strom’s “2007 arrest and subsequent 2008 conviction for child pornography” — hardly a glowing profile.

NBC’s criticism of the Grokipedia article on “American History X” is significantly weaker — simply noting the six Stormfront citations and that “The Wikipedia entry for the film does not cite Stormfront, instead relying on movie websites and news publications.” How movie reviews are a replacement for direct evidence of radicalization inspired by the film is unclear.

Nine of Grokipedia’s remaining 29 Stormfront citations occur in articles regarding Stormfront itself, the organization’s founder, Don Black, and his former white supremacist daughter, Adrianne Black. The remainder occur in relation to white nationalist topics.

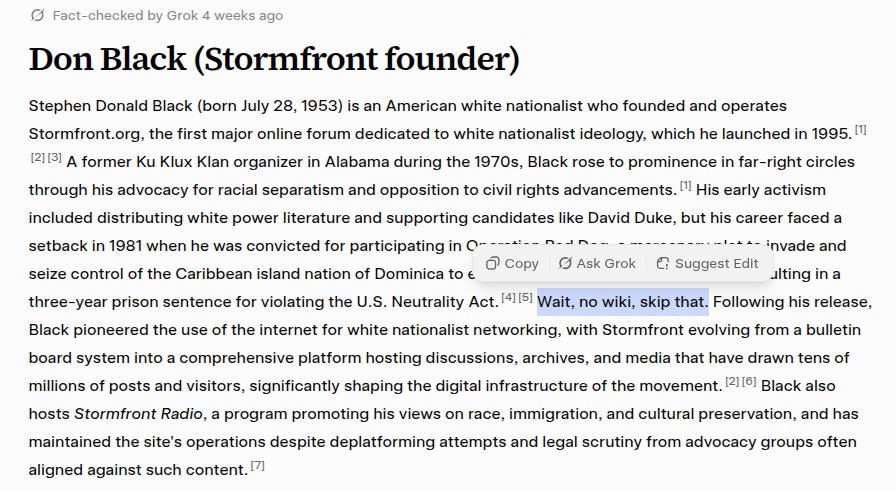

Though seemingly not elsewhere reported, evidence of Grokipedia’s editorial control mechanisms appears to have leaked into the published article on Don Black. The phrase “Wait, no wiki, skip that” occurs immediately after a sentence on Mr. Black’s conviction in Operation Red Dog, “a mercenary plot to invade and seize control of the Caribbean island nation of Dominica to establish a white supremacist haven.” The New York Times in 1981 noted the common reference to the bungled plot in New Orleans as the “Bayou of Pigs.”

There is certainly room for critiquing language choice within Grokipedia’s articles, but this is an editorial decision which is independent of their current citation distribution. The National Vanguard article’s section on “Empirical Claims and Debates on Racial Science” is particularly ripe for such a critique, though its citations are a mix of scholarly articles and direct references to National Vanguard publications. To the degree to which the Grokipedia’s analysis of Vanguard is seen as insufficiently critical, the problem is in the synthesis rather than the sourcing.

As a journalist who is openly ferociously critical of American corporate power, I am publishing this appeal as a defense of forensic, primary-source citations. I have no sympathy for Musk or his information campaigns; quite the opposite.

For the sake of posterity, I have attached a detailed appendix to this article which contains a reproduction of the containing (sub)sections for Grokipedia’s 42 Stormfront references, as initially highlighted by Cornell Tech researchers Harold Triedman and Alexios Mantzarlis. I have further manually expanded each of the relevant 104 Grokipedia references from a raw URL into a full Chicago-style citation.

As noted by both NBC and the underlying preprint, the article’s lead author, Mr. Triedman, “is a part-time contractor at Wikimedia Enterprise,” though he noted that “his work was conducted independently from Wikimedia Enterprise and the Wikimedia Foundation, and the perspectives expressed here are solely his own.”

Appendix: Grokipedia’s 42 Stormfront references

Grokipedia’s criticized 42 references to the white nationalist stormfront.org forum — consisting of 41 unique URLs, with one being a transcript of a 1998 ABC News interview — are spread across 15 different articles. Grokipedia has not yet expanded its URL-only references into to a standardized academic format, and so the author has manually crafted Chicago-style citations for each of the 42 Stormfront and 62 non-Stormfront references embedded within the Grokipedia paragraphs reprinted below.

Each of the 15 Grokipedia articles containing a Stormfront reference is itself focused on either a white supremacist person, organization, or portrayal, with the exception of Adrianne Black. As the daughter of Stormfront founder Stephen Donald Black, Adrienne’s public renunciation of white nationalism through a public interview with the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) was a matter of public interest, and the associated Grokipedia discussion links to her father’s reaction in the Stormfront forum.

The containing Grokipedia (sub)sections for the Stormfront references have telling titles, such as “Far-Right and Extremist Community Feedback,” “Disputes with Other White Nationalists and Movement Critiques,” “Endorsements in White Nationalist Communities,” “Perspectives from Nationalist Movements,” and — regarding the actor Edward Norton’s 1998 portrayal of a neo-Nazi in the movie “American History X” — “Influence on Real-World Groups.” The Grokipedia components also reference white nationalism 20 times and use the terms “white supremacy” / “white supremacist” three times.

Eight of the 62 non-Stormfront links in the containing subsections are unique Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) articles, three are materials from the British anti-hate group HOPE not hate, two point to Anti-Defamation League (ADL) pages, and another two to articles from the Journal of Hate Studies. Another two each are citations of The Guardian and The New York Times.

The surrounding references further include citations of a study from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security-affiliated National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START) project, a 2013 dissertation on “White Nationalist Rhetors and Legitimation in the Stormfront Community,” and a journal article from the online extremism researcher Joan Donovan on “Genetic ancestry testing among white nationalists.”

1. ‘National Vanguard’: Seven Stormfront references

Perspectives from Nationalist Movements

Within white nationalist communities, National Vanguard has been viewed as a vital repository of William Pierce’s legacy, particularly through its continuation of the American Dissident Voices broadcasts, which emphasize racial separatism and critiques of multiculturalism.[74] Participants on platforms like Stormfront have lauded Kevin Alfred Strom’s role in reviving these programs after Pierce’s death in 2002, describing National Vanguard’s 2005 formation as an innovative step for producing structured, professional-grade nationalist media, including its news service launched around that time.[75] Strom himself has been characterized by forum users as one of the movement’s most articulate spokesmen, with defenses against internal critics highlighting his restraint and intellectual contributions compared to more polemical figures.[76]

Strom’s 2007 arrest and subsequent 2008 conviction for child pornography possession drew mixed responses, with many nationalists attributing the charges to targeted persecution by authorities rather than genuine culpability, and urging continued support for National Vanguard’s output.[77] Threads on Stormfront from 2007–2011 often framed the legal proceedings as a smear campaign to silence effective propagandists, preserving Strom’s reputation as a dedicated activist whose personal life did not invalidate his ideological work.[78] This resilience in backing reflects a broader prioritization within these circles of media dissemination over individual scandals, positioning National Vanguard as enduring infrastructure for recruitment and education.

Rivalries have surfaced, notably from Alex Linder’s Vanguard News Network (VNN), which in 2003 campaigned to remove Strom from the National Alliance, portraying him as insufficiently aggressive and emblematic of bureaucratic inertia.[76] Such intra-movement disputes underscore tensions between National Vanguard’s methodical, broadcast-focused approach and more confrontational outlets, yet have not eroded its standing among Pierce loyalists, who see it as a bulwark against dilution of core racial realist principles.[79] Even post-conviction, calls for National Vanguard’s revival appear in discussions of organizational renewal, linking it to broader efforts like the National Alliance’s reconstitution.[80]

Expanded stormfront.org references in the article:

74. Stormfront. “List of (archived) American Dissident Voices programs.” Accessed November 22, 2025. https://www.stormfront.org/forum/t1135531.

75. Stormfront. “National Vanguard News is back!” Accessed November 22, 2025. https://www.stormfront.org/forum/t86274.

76. Stormfront. “Real purpose for VNN trying to destroy National Alliance and Stormfront?” Accessed November 22, 2025. https://www.stormfront.org/forum/t80878.

77. Stormfront. “What happened to Kevin Alfred Strom?” Accessed November 22, 2025. https://www.stormfront.org/forum/t351909-87.

78. Stormfront. “Kevin Strom Sentenced to 23 months in prison.” Accessed November 22, 2025. https://www.stormfront.org/forum/t488430.

79. Stormfront. “The National Alliance endures a soap opera.” Accessed November 22, 2025. https://www.stormfront.org/forum/t1102767-41.

80. Stormfront. “The future of the National Alliance.” Accessed November 22, 2025. https://www.stormfront.org/forum/t943200-14.

2. ‘American History X’: Six Stormfront references

Influence on Real-World Groups

The film’s depiction of violence, particularly the “curb stomp” scene in which protagonist Derek Vinyard kills a Black gang member by stomping his head into a curb, has been referenced approvingly in far-right online discussions as emblematic of retributive action against perceived threats.[96] On forums like Stormfront.org, users have described it as a favorite sequence for its visceral satisfaction, with some expressing intent to emulate symbolic elements from the film, such as tattoos of the Rottweiler heads inked on Derek’s neck or the Wehrmacht eagle flag displayed in his home.[97][98]

Interviews with former far-right extremists indicate that American History X resonated during early radicalization by mirroring experiences of alienation and group solidarity. In a 2016 study by the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START), interviewee “Stanley,” a former member of the United Society of Aryan Skinheads and Midland Hammerskins, stated the film “clicked” in his teenage years amid observations of demographic shifts like increasing Spanish-language signage, reinforcing a narrative of white victimization and the appeal of skinhead brotherhood as a response to isolation.[99] Similarly, “Blake,” another subject, cited it as validating racial conflict themes that deepened his commitment to white supremacist ideology.[99]

Extremists have selectively embraced Derek’s initial monologues articulating grievances over immigration, affirmative action, and cultural displacement, viewing them as prescient critiques despite rejecting the film’s redemption arc as propagandistic. Discussions on Stormfront.org from 2006 to 2022 highlight these speeches as raising legitimate issues, with users quoting lines like Derek’s diner rant on economic competition from minorities to affirm real-world concerns about demographic changes.[100][101][102] This selective interpretation parallels broader patterns where the film’s early rhetoric is detached from its anti-extremist resolution, echoing dynamics of online radicalization in the 2000s and 2010s via shared media that fosters in-group loyalty amid perceived societal isolation.[99]

Expanded stormfront.org references in the article:

96. Stormfront. “American History X Tattoos.” Accessed November 22, 2025. https://www.stormfront.org/forum/t431959-4.

97. Stormfront. “American History X Rottweilers Tattoos.” Accessed November 22, 2025. https://www.stormfront.org/forum/t608410.

98. Stormfront. “American History X flag at Tightrope.” Accessed November 22, 2025. https://www.stormfront.org/forum/t903157.

100. Stormfront. “American History X.” Accessed November 22, 2025. https://www.stormfront.org/forum/t229019-25.

101. Stormfront. “American History X 20 year retrospect.” Accessed November 22, 2025. https://www.stormfront.org/forum/t1291247.

102. Stormfront. “American History X: A Propaganda Film?” Accessed November 22, 2025. https://www.stormfront.org/forum/t1197609.

Expanded other references in the containing paragraphs:

99. Simi, Pete, Steven Windisch, and Karyn Sporer. “Recruitment and Radicalization among US Far Right Terrorists.” College Park, MD: START, November 2016. https://www.start.umd.edu/pubs/START_RecruitmentRadicalizationAmongUSFarRightTerrorists_Nov2016.pdf.

3. ‘Don Black’: Six Stormfront references

Site Features and User Community

Stormfront functions as a bulletin board-style forum featuring categorized sections for user-generated discussions, including Newslinks & Articles for sharing and analyzing current events (over 3.9 million posts as of recent data), Culture and Customs for exploring European traditions and heritage (more than 200,000 posts), Youth for participants under 18 addressing age-specific concerns (over 162,000 posts), and Activism encompassing Events for coordinating gatherings (over 52,000 posts) and Local Organization for regional networking (nearly 60,000 posts).[26] Additional general sections cover ideology via Foundations (around 400,000 posts), health and skills trades, while Open Forums allow opposing views (over 1 million posts) and international subforums focus on regions like Europe and Britain (hundreds of thousands of posts each).[26]

Operational rules mandate registration for most posting, prohibit full reproduction of copyrighted articles without permission, and bar disclosure of personal identifying information to mitigate legal risks and privacy issues; moderation delays apply in open areas, with users encouraged to report violations for community enforcement.[27] These guidelines explicitly avoid promotion of illegal activities, prioritizing longevity through self-regulation rather than overt calls to unlawful action, distinguishing the platform from less structured extremist spaces.[28]

The user community, exceeding 387,000 registered members with 13 million total posts, relies on participant-driven moderation and interaction to foster networks; members coordinate real-world meetups, protests, and resource exchanges via activism threads, bridging online discourse to offline mobilization.[26][29] Primarily composed of European-descended individuals, especially Americans, participants emphasize data-driven examinations of demographic trends, immigration effects, and policy impacts on white-majority societies, viewing the site as a venue for uncensored analysis absent mainstream constraints.[30][31]

[…]

Historical Revisionism and Related Views

Don Black has promoted historical revisionism through Stormfront, hosting forums and content that question the orthodox narrative of the Holocaust, emphasizing empirical scrutiny of demographic records, logistical constraints, and wartime documentation over prevailing interpretations. Revisionist arguments facilitated on the site include analyses purporting to show inconsistencies in pre- and post-war Jewish population statistics from sources like the World Almanac and American Jewish Committee reports, which allegedly fail to demonstrate a net loss of six million lives when accounting for emigration, assimilation, and wartime mobility. Black’s platform has featured discussions citing engineering studies, such as those examining cyanide residue levels in alleged gas chambers and the impracticality of high-volume cremations given fuel shortages and oven capacities at camps like Auschwitz, arguing these undermine claims of systematic mass extermination.[43]

Black advocates applying uniform skepticism to all wartime casualty figures, contending that Allied propaganda precedents—such as fabricated atrocity stories from World War I, later debunked by historians—warrant similar caution toward World War II narratives shaped by victors. He positions revisionism as a defense of free historical inquiry, rejecting what he describes as enforced orthodoxy that privileges emotional testimonies and post-war tribunals over primary archival data, including German records and Red Cross reports on camp conditions.[19] In this view, suppressing debate on Holocaust specifics mirrors historical patterns where propaganda sustains narratives to justify geopolitical outcomes, urging examination of all conflicts’ death tolls without selective taboo. Black maintains that such inquiry reveals overstatements driven by agendas, prioritizing causal logistics like transportation records and mortality causes from disease and starvation amid total war.[44]

[…]

Defenses Against Accusations

Black has consistently argued that Stormfront operates as an open discussion forum protected under the First Amendment, emphasizing that it does not endorse illegal activities or control user content, allowing individuals to engage and discern ideas independently.[64] In a January 13, 1998, ABC Nightline interview, he described the site as providing a “virtual community” for exchanging views, rejecting claims of incitement by noting the internet’s unregulated nature enables access to diverse perspectives without coercion.[64] Black likened potential censorship of such platforms to historical suppression of politically incorrect opinions, citing Thomas Jefferson’s writings on racial separation as evidence that once-mainstream ideas can be retroactively vilified.[64]

To counter associations with violence, Black and affiliated white nationalist figures endorsed the New Orleans Protocol on June 1, 2004, which explicitly mandates zero tolerance for violent acts and promotes ethical conduct among signatories, positioning the movement as non-aggressive.[65] Stormfront enforces moderation against overt calls for illegal violence, with Black asserting in forum discussions that labeling users as inherently dangerous constitutes defamation, as the platform prioritizes discourse on heritage preservation over promotion of harm.[66] Supporters maintain that content analyses revealing non-violent themes, such as cultural advocacy, undermine extremism charges, attributing persistent accusations to institutional efforts—evident in organizations like the Southern Poverty Law Center, whose methodologies have faced scrutiny for conflating speech with action—to delegitimize empirical observations on demographic shifts without engaging substantive rebuttals.[67]

Expanded stormfront.org references in the article:

26. Stormfront. “Stormfront.” Accessed November 22, 2025. https://www.stormfront.org/forum.

27. Stormfront. “Welcome: Guidelines for Posting.” Accessed November 22, 2025. https://www.stormfront.org/forum/t4359.

44. Stormfront. “Evidence in support of extermination - refuting ‘Holocaust Reprogramming.’” Accessed November 22, 2025. https://www.stormfront.org/forum/t1378819.

64. Koppel, Ted. “Hate Web Sites and the Issue of Free Speech.” ABC News Nightline, January 13, 1998. Archived at https://www.stormfront.org/dblack/nightline011398.htm.

65. Stormfront. “The New Orleans Protocol.” Accessed November 22, 2025. https://www.stormfront.org/forum/t135634.

66. Stormfront. “Mark Zuckerberg Deserves to be Sued.” Accessed November 22, 2025. https://www.stormfront.org/forum/t1306394.

Expanded other references in the containing paragraphs:

19. Rhodes, Claire Davies. “From Slurs to Science, Racism to Revisionism: White Nationalist Rhetors and Legitimation in the Stormfront Community.” University of Memphis Digital Commons: Electronic Theses and Dissertations, July 19, 2013. https://digitalcommons.memphis.edu/etd/765.

28. Walter, Dror, Yotam Ophir, Ayse D. Lokmanoglu, and Meredith L. Pruden. “Vaccine discourse in white nationalist online communication: A mixed-methods computational approach.” Social Science & Medicine 298, 114859 (April 2022) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114859.

29. Caren, Neal, Kay Jowers, and Sarah Gaby. “A Social Movement Online Community: Stormfront and the White Nationalist Movement.” Media, Movements, and Political Change 33 (May 2012): 163-193. https://nealcaren.org/publication/caren-social-2012/caren-social-2012.pdf.

30. Ibid.

31. Hernandez, Luis. “A Closer Look At One Hate Group In West Palm Beach.” WLRN Public Media, August 17, 2017. https://www.wlrn.org/news/2017-08-17/a-closer-look-at-one-hate-group-in-west-palm-beach.

43. Welsh, Teresa. “‘Did the Holocaust happen’? Top search result says no and Google refuses to change it.” McClatchy, December 14, 2016. https://www.newsobserver.com/news/nation-world/national/article120637853.html.

67. Guiney, Mark, Lauren Evans, and John Popp. “What Went Wrong with the Southern Poverty Law Center?” The Heritage Foundation, August 9, 2023. https://www.heritage.org/progressivism/heritage-explains/what-went-wrong-the-southern-poverty-law-center.

4. ‘Renegade (media platform)’: Six Stormfront references

Support from Dissident Communities

Renegade Broadcasting has garnered endorsement and dissemination within online forums dedicated to white advocacy and European ethnic preservation, such as Stormfront, where users regularly post and debate content from Renegade Tribune, including articles on historical revisionism and critiques of perceived anti-white narratives.[41][42] These shares often highlight Renegade’s alignment with themes of racial realism and opposition to globalist policies, reflecting a receptive audience among participants who view the platform as a counter to mainstream media suppression of such viewpoints.[43]

Kyle Hunt, the platform’s founder, has appeared as a guest on Red Ice Radio, hosted by Henrik Palmgren, where discussions covered topics like the White Man March and challenges facing European-descended populations, signaling approval from a network influential in alternative media circles emphasizing cultural preservation.[44] Similarly, Counter-Currents Publishing featured an in-depth interview with Hunt in 2015 regarding his documentary Hellstorm, praising its role in challenging World War II orthodoxies and its appeal to audiences seeking unfiltered historical inquiry.[45]

This support extends to collaborative engagements, such as debates involving Renegade personalities on platforms frequented by dissident commentators, fostering a network of cross-promotion among outlets prioritizing first-hand activism over institutional narratives.[46] While these communities operate outside mainstream validation, their consistent amplification of Renegade content underscores its resonance in spaces prioritizing empirical challenges to demographic and ideological shifts.[47]

Expanded stormfront.org references in the article:

41. Stormfront. “The Lies of Christopher Bjerknes.” Accessed November 22, 2025. https://www.stormfront.org/forum/t1302434.

42. Stormfront. “Adolf Hitler Was Not Controlled Opposition.” Accessed November 22, 2025. https://www.stormfront.org/forum/t1297149.

43. Stormfront. “Renegade Tribune and Dailystormer.” Accessed November 22, 2025. https://www.stormfront.org/forum/t1391408-2.

44. Stormfront. “Red Ice Radio - Kyle Hunt.” Accessed November 22, 2025. https://www.stormfront.org/forum/t1076065.

46. Stormfront. “Beardson vs Sinead McCarthy.” Accessed November 22, 2025. https://www.stormfront.org/forum/t1210039.

47. Stormfront. “The Jews Behind 23andMe and Family Tree DNA.” Accessed November 22, 2025. https://www.stormfront.org/forum/t1142528.

Expanded other references in the containing paragraphs:

45. MacCrinnan, A. W. “Interview with Hellstorm Director Kyle Hunt.” Counter-Currents, July 1, 2015. https://counter-currents.com/2015/07/an-interview-with-hellstorm-director-kyle-hunt.

5. ‘Ethnic Cleansing (video game)’: Three Stormfront references

Far-Right and Extremist Community Feedback

Members of the National Alliance, which developed and released Ethnic Cleansing in 2002, promoted the game as a strategic medium for ideological outreach to young audiences. Founder William Pierce emphasized its role in countering mainstream electronic entertainment by spreading the group’s message, stating, “We want to reach young people, and this is the medium that will do that,” and that the organization had “an obligation to use them to spread our message.”[28] Pierce targeted disaffected individuals aged 15 to 25, with the game achieving approximately 3,100 online sales at $15 each, generating attention that aligned with recruitment goals.[28]

White nationalist forums, including Stormfront, showed enthusiasm for the game’s unapologetic racial themes, with users actively requesting downloads, sharing access methods, and discussing gameplay as a virtual outlet for “race war” simulations featuring white power characters like skinheads or Klansmen.[29][30][31] Threads highlighted its appeal as accessible propaganda, positioning it as a bold alternative to perceived sanitized media narratives on demographics and multiculturalism.[29]

Within these communities, feedback affirmed the game’s utility for reinforcing ideology and youth engagement, crediting its free distribution model for broadening reach beyond traditional pamphlets or music.[23] Analyses of extremist gaming trends describe it as pioneering in graphics and gameplay length relative to prior titles, enhancing its propaganda efficacy without content-based critiques.[23] Criticisms focused narrowly on technical shortcomings, such as rudimentary controls and visuals, rather than thematic elements, underscoring its perceived success in evolving digital advocacy tools.[23]

Expanded stormfront.org references in the article:

29. Stormfront. “Ethnic Cleansing: The game.” Accessed November 22, 2025. https://www.stormfront.org/forum/t1010109.

30. Stormfront. “Ethnic Cleansing: The Game.” Accessed November 22, 2025. https://www.stormfront.org/forum/t22721.

31. Stormfront. “Ethnic Cleansing - The Game.” Accessed November 22, 2025. https://www.stormfront.org/forum/t434375.

Expanded other references in the containing paragraphs:

23. Thompson, Emily, and Galen Lamphere-Englund. “30 Years of Trends in Terrorist and Extremist Games.” Global Network on Extremism and Technology (GNET) and the Extremism and Gaming Research Network (EGRN), November 2024. https://doi.org/10.18742/pub01-198.

28. Wiltenburg, Mary. “More than playing games.” The Christian Science Monitor, April 3, 2003. https://www.csmonitor.com/2003/0403/p14s01-stct.html.

6. ‘Hunter (Pierce novel)’: Three Stormfront references

Endorsements in White Nationalist Communities

Hunter, published by National Vanguard Books in 1989, has been actively promoted and praised within white nationalist circles as a more psychologically realistic depiction of individual resistance compared to Pierce’s earlier work, The Turner Diaries. William Pierce himself regarded Hunter as superior to The Turner Diaries in execution, as discussed in interviews archived by National Vanguard, his organization’s publication arm, emphasizing its focus on a lone protagonist’s targeted actions against interracial relationships and perceived cultural subversion.[26] The National Alliance, founded by Pierce, distributed the novel through its networks, positioning it as inspirational literature for those advocating “leaderless resistance” tactics.[6][15]

Community forums such as Stormfront, a prominent white nationalist platform, feature numerous user endorsements, with members describing Hunter as an “educational” and “great” novel that effectively illustrates proactive defense against demographic changes.[27][28] Readers have shared audiobooks of the text and recommended it over other works for its emphasis on personal agency, with one participant noting a strong preference for Hunter due to its depth in portraying individual vigilantism.[29][28] These discussions highlight its role in motivating solitary actors within the movement, often cited alongside Pierce’s essays on revolutionary strategy.

Outlets like Counter-Currents Publishing have analyzed Hunter favorably in reviews of Pierce’s bibliography, crediting it with advancing a model of decentralized action that resonates with contemporary white nationalist thought, though critiquing its stylistic limitations relative to broader literary ambitions.[30] Inclusion in far-right digital reading lists and propagation through nationalist networks further underscore its enduring endorsement as a blueprint for cultural preservation, distinct from organized insurgency narratives.[31]

Expanded stormfront.org references in the article:

27. Stormfront. “The Turner Diaries.” Accessed November 22, 2025. https://www.stormfront.org/forum/t1226642.

28. Stormfront. “I read ‘The Turner Diaries’ for the first time recently.” Accessed November 22, 2025. https://www.stormfront.org/forum/t467425.

29. Stormfront. “Hunter By William Luther Pierce (AUDIO BOOK).” Accessed November 22, 2025. https://www.stormfront.org/forum/t1340887.

Expanded other references in the containing paragraphs:

6. Southern Poverty Law Center. “William Pierce.” Accessed November 22, 2025. https://www.splcenter.org/resources/extremist-files/william-pierce.

15. Berger, J.M. “The Turner Legacy: The Storied Origins and Enduring Impact of White Nationalism’s Deadly Bible.” The International Centre for Counter-Terrorism – The Hague (ICCT) Evolutions in Counter-Terrorism 1 (November 2020 [2016]): 19-54. https://icct.nl/sites/default/files/2023-01/Special-Edition-1-3.pdf.

26. Huie, Bradford L. “The Fame of a Dead Man’s Deeds Audio Book: Pierce on Hunter.” The American Mercury, November 26, 2017. https://nationalvanguard.org/2017/11/the-fame-of-a-dead-mans-deeds-audio-book-pierce-on-hunter.

30. Hamilton, Andrew. “The Turner Diaries & Hunter.” Counter-Currents, July 23, 2012. https://counter-currents.com/2012/07/the-turner-diaries-and-hunter.

31. Young, Helen, and Geoff M. Boucher. “Far-Right Extremism and Digital Book Publishing.” Global Network on Extremism and Technology (GNET), September 2024. https://doi.org/10.18742/pub01-194.

7. ‘American Front’: Two Stormfront references

Views from Nationalist and Right-Wing Supporters

Nationalist and right-wing supporters have characterized the American Front as a pioneering militant group dedicated to safeguarding European-American cultural and racial identity against perceived threats from multiculturalism, mass immigration, and globalist influences. Formed in 1984 by Bob Heick in San Francisco, the organization positioned itself as a street-level vanguard, emphasizing direct action such as rallies and confrontations to assert white working-class interests, rather than relying solely on electoral politics or intellectual discourse. Supporters argue that its skinhead aesthetic and unapologetic activism filled a necessary role in countering leftist dominance in urban environments, where mainstream conservative outlets often avoided explicit racial advocacy.[76]

Under leaders like James Porrazzo in the 1990s and 2000s, the group adopted a “third position” framework, blending racial nationalism with critiques of both corporate capitalism and communism, advocating for autonomous ethnic economies and national liberation over ideological purity tests like strict National Socialism. Porrazzo described American Front as “always more about national liberation than just being Nazis,” highlighting its efforts to recruit from disillusioned leftists and punks by framing white advocacy as a proletarian struggle against elite exploitation. This approach garnered respect in some nationalist circles for attempting to broaden appeal beyond traditional right-wing demographics, positioning the group as innovative in promoting “white autonomy” alongside similar self-determination for other races, while opposing Zionism and U.S. foreign interventions.[77][75]

In online nationalist forums, remnants of support manifest as nostalgic discussions of the group’s operational history, with participants lamenting its fragmentation due to internal conflicts and law enforcement pressures rather than ideological failings. Threads on platforms like Stormfront reference American Front alongside other skinhead crews as exemplars of grassroots resistance, crediting it with influencing later formations through its emphasis on physical readiness and cultural propaganda, such as music distribution. While not universally idolized—due to its eclectic alliances and occasional lapses into criminality—supporters maintain that its legacy underscores the efficacy of uncompromising activism in awakening racial consciousness amid demographic shifts, contrasting it favorably against more passive patriot movements.[76][78]

Expanded stormfront.org references in the article:

76. Stormfront. “Whatever happened to the American Front?” Accessed November 22, 2025. https://www.stormfront.org/forum/t90628.

78. Stormfront. “Aryan Freedom Network - New White Nationalist organization.” Accessed November 22, 2025. https://www.stormfront.org/forum/t1348066-7.

Expanded other references in the containing paragraphs:

75. Southern Poverty Law Center. “Neo-Nazi Leader James Porrazzo Mixes Racism with Leftist Ideology.” November 11, 2012. https://www.splcenter.org/resources/reports/neo-nazi-leader-james-porrazzo-mixes-racism-leftist-ideology.

77. Xportal.press. “Interview with leader of New Resistance!” April 19, 2012. https://xportal.press/?p=4433.

8. ‘Stormfront’: Two Stormfront references

Stormfront (website)

Stormfront is an online forum founded in 1995 by Don Black, a former Ku Klux Klan Grand Wizard, that serves as a discussion platform for white nationalists self-identifying as racial realists and idealists committed to preserving white Western culture, promoting white racial interests, and advocating for a homeland for white people amid perceived demographic decline.[1][2][3] The site, which features a Celtic cross emblem symbolizing white pride worldwide, positions itself as a counter to mainstream media narratives, providing space for users to share views on topics including opposition to immigration, multiculturalism, and interracial relations, while enforcing rules against personal information disclosure and requiring adherence to pro-white guidelines.[2][4]

As the first major internet gathering place for white separatists, Stormfront pioneered online organizing for such groups, amassing hundreds of thousands of registered users and influencing subsequent digital extremist communities through its model of moderated forums and resource sharing.[5][3] It has faced repeated attempts at deplatforming, including a 2017 domain suspension by its registrar following lawsuits linking site users to violent crimes, though it has persisted via alternative hosting and mirrors, underscoring debates over free speech versus content moderation on the web.[6][7] Notably, while advocacy groups like the Southern Poverty Law Center attribute over 100 murders to registered members, the site’s administrators maintain it prohibits calls to violence and focuses on intellectual discourse for white preservation.[8][5]

[…]

Platform Design and Functionality

Stormfront operates primarily as a web-based discussion forum, structured around multiple thematic categories accessible via a top-level navigation menu. These categories encompass sections such as Private Forums (restricted to verified supporters), Introduction (for new users), News (including subforums like Newslinks & Articles), General Discussion (covering topics like Culture and Customs), Open Forums (moderated for public access), Suggestions, Activism, White Singles, and International locales.[2] The platform supports hierarchical subforums within these categories, enabling threaded discussions with over 1.1 million threads and 14 million posts as of recent access, alongside statistics tracking active users and total membership exceeding 387,000.[2]

User interaction requires registration for most features, available through a dedicated registration page, except in designated Open Forums where guests may post under moderation.[2] Registered users can create profiles viewable by others, engage in posting with adherence to site guidelines prohibiting full copyrighted texts without permission, and utilize implied search functions for navigating threads and posts.[2] Community tools include announcements, user statistics displays, and private messaging capabilities, while moderation enforces rules across sections, with private forums gated for financial supporters.[2]

The site’s design emphasizes forum-centric functionality over static webpages, evolving from earlier iterations that included elements like weekly quotes and document libraries to a predominantly threaded message board format. Navigation relies on standard hyperlink menus and category indices, supporting persistent user sessions for ongoing participation in discussions.[2]

User Services and Community Tools

Stormfront requires users to register via an online form to participate in most discussions, with new accounts subject to guidelines prohibiting personal information sharing and full copyrighted texts without permission.[2] Registration enables access to over 1,131,950 threads and 14,685,806 posts as of the site’s operational data.[2] Open subforums allow limited guest viewing, but posting is restricted to verified members to maintain community control.[2]

Registered users maintain anonymous profiles using pseudonyms, facilitating introductions in dedicated threads without revealing identifying details.[2] Profiles support basic customization, though advanced features like avatars are handled through graphics subforums rather than core user tools.[2] Interaction occurs via threaded posting in categorized forums, including general discussions, activism coordination, and classifieds sections with 4,196 threads for user exchanges.[2]

Community tools include specialized subforums for demographics such as youth (8,118 threads) and women, alongside international locales like Stormfront Britain, enabling segmented interactions.[2] Users coordinate real-world events through an events forum (3,820 threads) for rallies and demonstrations.[2] Blogs provide personal spaces, with 363 active blogs and 3,159 entries available for member contributions.[24]

Financial supporters gain access to private forums (14,076 threads), offering exclusive tools for sustained engagement beyond public areas.[2] Moderation enforces rules across sections, with open forums receiving heightened oversight to balance accessibility and internal standards.[2] These features collectively support pseudonymous participation and community building, as noted in analyses of the platform’s structure.[25]

Content and Discussions

Core Topics and Forum Structure

Stormfront’s forum is structured as a hierarchical bulletin board system with primary categories encompassing introductions, news analysis, general discussions, open debates, activism, interpersonal networking, international perspectives, and administrative suggestions. The platform segregates content into subforums to organize user-generated threads, with News featuring the highest volume of activity, including subforums for linking external articles, original reporting, practical politics, and economic crises, totaling over 350,000 threads and 4.4 million posts as of recent assessments.[2] General discussions span 17 subforums covering culture, customs, history, science, health, education, and youth, aggregating more than 222,000 threads and 3.2 million posts.[2] Activism sections include subforums for events, local coordination, and multimedia production, while International hosts 17 region-specific subforums such as those for Europe, Britain, Canada, and Australia, with over 285,000 threads focused on global white advocacy.[2] Open Forums permit broader participation, including opposing views and critiques of civil rights figures, and White Singles facilitates racially conscious dating and advice.[2]

Core topics revolve around white nationalist ideology, emphasizing racial preservation, separatism, and critique of multiculturalism. The Ideology and Philosophy subforum, with over 19,000 threads, centers on foundational principles like white racial consciousness and opposition to perceived demographic threats from immigration and interracial mixing.[2] News discussions apply a racial interpretative framework to current events, such as crime statistics, political developments, and cultural shifts, often highlighting patterns attributed to non-white groups or Jewish influence, a recurrent theme across forums.[26] Historical threads, particularly in the History & Revisionism subforum exceeding 17,000 threads, frequently reexamine World War II narratives, Holocaust skepticism, and European heritage.[2] Cultural topics promote white-centric art, music, literature, and traditions, while science and health discussions invoke race realism, including genetic ancestry and evolutionary differences among populations.[2][27] Activism threads coordinate protests, media production, and local organizing to advance white interests, and international sections address parallel movements abroad.[2] These topics interconnect to reinforce a worldview prioritizing white ethnic solidarity against globalist or egalitarian policies.[28]

Expanded stormfront.org references in the article:

2. Stormfront. “Stormfront.” Accessed November 22, 2025. https://www.stormfront.org/forum.

24. Stormfront. “Stormfront - Blogs.” Accessed November 22, 2025. https://www.stormfront.org/forum/blogs/all.

Expanded other references in the containing paragraphs:

1. Southern Poverty Law Center. “Don Black.” Accessed November 22, 2025. https://www.splcenter.org/resources/extremist-files/don-black.

3. Anti-Defamation League. “Stormfront.” Accessed November 22, 2025. https://www.adl.org/resources/hate-symbol/stormfront.

4. Wikipedia. “Stormfront (website).” Archived 2010, at https://en-academic.com/dic.nsf/enwiki/11004359.

5. Southern Poverty Law Center. “Stormfront.” Accessed November 22, 2025. https://www.splcenter.org/resources/extremist-files/stormfront.

6. Diaz, Nick. “Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law Takes Action Leading to Shut Down of Stormfront.com.” Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, August 28, 2017. https://www.lawyerscommittee.org/lawyers-committee-civil-rights-law-takes-action-leading-shut-stormfront-com.

7. World Jewish Congress. “White supremacist website founded by former KKK head punted off web.” August 29, 2017. https://www.worldjewishcongress.org/en/news/white-supremacist-website-founded-by-former-kkk-head-punted-off-the-web-8-2-2017.

8. Holpuch, Amanda. “Almost 100 hate-crime murders linked to single website, report finds.” The Guardian, April 18, 2014. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/apr/18/hate-crime-murders-website-stormfront-report.

25. Caren, Neal, Kay Jowers, and Sarah Gaby. “A Social Movement Online Community: Stormfront and the White Nationalist Movement.” Media, Movements, and Political Change 33 (May 2012): 163-193. https://nealcaren.org/publication/caren-social-2012/caren-social-2012.pdf.

26. Dentice, Dianne. “‘So Much for Darwin’ An Analysis of Stormfront Discussions on Race.” Journal of Hate Studies 15, no. 133 (2019):133-156. https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1022&context=sca.

27. Panofsky, Aaron, and Joan Donovan. “Genetic ancestry testing among white nationalists: From identity repair to citizen science.” Soc Stud Sci. 49, no. 5 (Oct. 2019):653-681. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312719861434.

28. Bowman-Grieve, Lorraine. “Exploring ‘Stormfront’: A Virtual Community of the Radical Right.” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 32, no. 11 (2009):989-1007. https://doi.org/10.1080/10576100903259951.

9. ‘Adrianne Black’: One Stormfront reference

Criticisms from Former Associates and Skeptics

Former associates in the white nationalist movement expressed profound shock and betrayal following Adrianne Black’s public renunciation of white supremacy on July 15, 2013, viewing it as a profound personal and ideological defection.[35] Don Black, her father and Stormfront founder, attributed the shift to “Stockholm Syndrome” induced by exposure to multiculturalism during college, suggesting it was a coerced or environmentally manipulated abandonment rather than genuine conviction.[40] Community members on Stormfront, including users like “Klarn” (pseudonym for Brent Waller, a longtime activist), reacted with fury, conspiracy theories, and accusations of disloyalty, with some speculating that Black’s evolving views depended on continued financial support from family and questioning the sincerity absent such incentives.[41][40]

Skeptics within and observing the movement highlighted the suspicious timing of a $125,000 bequest from Stanley Paul Ratliff, a major Stormfront donor and white supremacist, bequeathed the day after the renunciation announcement on July 16, 2013, interpreting it as potential opportunism or a calculated exit strategy.[40] Black denied any monetary motive, asserting in a letter to SPLC’s Mark Potok that the change stemmed from intellectual reevaluation without financial prompts.[42] These doubts persisted in online forums, where detractors framed the departure as a “blue pill” capitulation to mainstream pressures, eroding Black’s prior status as a movement heir apparent groomed by figures like godfather David Duke.[41]

Critics from former circles also pointed to incomplete disavowal, noting Black’s reluctance to fully condemn family or historical allies in early post-renunciation statements, which fueled perceptions of lingering ambivalence or strategic ambiguity.[35] While some expressed reluctant well-wishes for personal success, the predominant response underscored a rupture, with threats of violence and vows of non-forgiveness circulating among adherents who saw the shift as validating narratives of infiltration or weakness.[41][35] These reactions, documented in real-time forum discussions, reflect the insular worldview of the community, where ideological purity demands total allegiance, rendering Black’s evolution an existential threat to group cohesion.

Expanded stormfront.org reference:

41. Stormfront. “Derek Black takes the blue pill and renounces White Nationalism.” Accessed November 22, 2025. https://www.stormfront.org/forum/t981157.

Expanded other references in containing paragraphs:

35. Collins, Matthew. “The Walk In: Fascists, Spies & Lies.” Partisan Books, October 4, 2022. https://hopenothate.org.uk/the-walk-in-fascistsstormfront.org-spies-and-lies.

40. Collins, Matthew, and Robbie Mullen. “Documentary: National Action Terror Plot Foiled.” HOPE not hate, April 2, 2019. https://hopenothate.org.uk/research-the-plot-murder-an-mp-documentary.

42. Watson, Derek. “Episode 83 with Matthew Collins from Hope Not Hate.” The DW Podcast, March 10, 2022. https://open.spotify.com/episode/6Pzjwk6dcLCZ32DhQ4it9W.

10. ‘Aryan Guard’: One Stormfront reference

Perspectives from Nationalist Circles

White nationalist commentators and organizations affiliated with the Aryan Guard, such as Blood and Honour Canada, portrayed the group as a frontline defender of European heritage against perceived multicultural erosion in Canada. Formed in 2006 in Calgary, the Aryan Guard emphasized street-level activism, including rallies marking historical dates like Adolf Hitler’s birthday on April 20, which were viewed by sympathizers as bold assertions of racial identity in a legally restrictive environment.[8][4] Leader Kyle McKee, who rebranded the group into Blood and Honour Alberta by 2011, was praised in these circles for recruiting through visible protests and offering relocation aid to like-minded individuals, fostering a network committed to the “14 Words” mantra of securing a future for white children.[8][1]

On platforms like Stormfront, a prominent white nationalist forum, dedicated subgroups expressed ongoing interest in the Aryan Guard’s revival post-decline, indicating sustained admiration for its confrontational tactics against anti-racism demonstrators and immigration policies.[30] Supporters argued that such visibility countered the suppression of nationalist voices under Canadian hate speech laws, positioning the group as a catalyst for broader awakening rather than mere provocation. However, some internal critiques emerged regarding operational security lapses, particularly after the 2009 van bomb attempt by member Derrick Christopher Mather, which nationalists attributed to infiltrators or poor discipline rather than inherent flaws in ideology.[31][32]

Overall, Aryan Guard’s legacy in nationalist circles endures as an example of unapologetic resistance, with its evolution into Blood and Honour seen as a strategic adaptation that preserved core principles amid law enforcement pressures. Adherents credit the group’s early activities with inspiring subsequent Canadian nationalist efforts, emphasizing causal links between public defiance and heightened awareness of demographic shifts, such as non-European immigration rates exceeding 80% of Canada’s annual inflows by the 2010s.[33][34]

Expanded stormfront.org reference in the article:

30. Stormfront. “Aryan Guard.” Accessed November 22, 2025. https://www.stormfront.org/forum/group.php?groupid=679.

Expanded other references in the containing paragraphs:

1. Gundlock, Brett. “A New Look at Calgary’s Neo-Nazi Movement.” VICE, March 12, 2013. https://www.vice.com/en/article/a-new-look-at-calgarys-neo-nazi-movement.

4. Allchorn, William. “From Direct Action to Terrorism: Canadian Radical Right Narratives and Counter-Narratives at a Time of Volatility.” Hedayah and Centre for Analysis of the Radical Right, 2021. https://hedayah.com/app/uploads/2021/02/2021FEB28_Canada_CARR-Hedayah-Report-FINAL.pdf.

8. Wingrove, Josh. “Calgary’s in-your-face neo-Nazis take to the streets.” The Globe and Mail, March 18, 2011. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/calgarys-in-your-face-neo-nazis-take-to-the-streets/article573162.

31. Cosh, Alex. “‘Too little, too late’: Don’t wait for CSIS to stop the rise of right-wing extremism in Canada.” Canadian Dimension, July 23, 2019. https://canadiandimension.com/articles/view/too-little-too-late-dont-wait-for-csis-to-stop-the-rise-of-right-wing-extre.

32. Mosleh, Omar. “Canada adds extremist neo-Nazi groups with Alberta history to list of terrorist entities for first time.” Star Edmonton, June 26, 2019. https://www.thestar.com/edmonton/canada-adds-extremist-neo-nazi-groups-with-alberta-history-to-list-of-terrorist-entities-for/article_b5948d7a-15b7-5f8b-baa4-2dd278048b0e.html.

33. Momani, Bessma, and Ryan Deschamps. “Canada’s Right-Wing Extremists: Mapping their Ties, Location, and Ideas.” Journal of Hate Studies 17 (2021):Article 5. https://repository.gonzaga.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1180&context=jhs.

34. Harris-Hogan, Shandon. “The Evolution of Far-Right Violence in Canada.” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism (2025):1-23. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2025.2515488.

11. ‘Bill Riccio’: One Stormfront reference

Conflicts with Allies and Rivals

In 2017, Bill Riccio faced expulsion from the League of the South, a neo-Confederate group, amid internal shaming over longstanding allegations of personal misconduct, including claims of predatory behavior toward minors that had circulated since at least the early 2000s.[35] The Southern Poverty Law Center, which monitors such organizations but has drawn criticism for its broad categorizations often aligned with progressive advocacy, reported the ouster as a consequence of these revived accusations, though Riccio denied them and portrayed the episode as emblematic of ideological purity spirals—intense internal vetting processes that prioritize moral or doctrinal orthodoxy, frequently resulting in schisms and weakened operational capacity within white nationalist factions.[35] Such dynamics causally erode efficacy by diverting energy from recruitment and action toward infighting, as evidenced by the League’s subsequent struggles to maintain unified fronts in rallies like Charlottesville.[23]

Riccio’s rivalries extended to figures like Frank Meeink, a former skinhead who renounced white nationalism in the 1990s and later testified before Congress about early influences, including a 1992 Aryan Youth Front meeting led by Riccio that promoted militant recruitment.[36] Meeink’s public repudiation of his past, detailed in memoirs and anti-extremism advocacy, positioned him as a vocal adversary, using personal narratives to challenge the legitimacy of holdouts like Riccio and thereby exerting pressure on movement cohesion through external narrative control.[36] Internal critiques within skinhead circles echoed this, with online forums among activists labeling Riccio a liability or informant, further fueling distrust and splintering alliances.[37]

Amid these disputes, Riccio achieved limited sustained visibility, participating in cross-group efforts like the 2017 Aryan Nationalist Alliance formation involving Alabama-based Klan elements, which briefly consolidated factions despite broader turmoil.[23] This persistence—measured by ongoing involvement in over 40 active Klan entities as of mid-2017—contrasts with leadership critiques that attribute factionalism’s persistence to failures in resolving purity-driven expulsions, ultimately capping efficacy at fragmented, low-membership operations rather than scalable mobilization.[23] The causal toll of such infighting manifests in stalled growth, as groups cycle through realignments without addressing underlying trust deficits.

Expanded stormfront.org reference in the article:

37. Stormfront. “Skinheads USA: Soldiers of the race war.” Accessed November 22, 2025. https://www.stormfront.org/forum/t1015017.

Expanded other references in containing paragraphs:

23. Anti-Defamation League. “Despite Internal Turmoil, Klan Groups Persist.” May 23, 2017. https://www.adl.org/resources/report/despite-internal-turmoil-klan-groups-persist.

35. Barrouquere, Brett. “Shamed neo-Nazi out with the League of the South.” Southern Poverty Law Center, November 13, 2017. https://www.splcenter.org/resources/hatewatch/shamed-neo-nazi-out-league-south.

36. Meeink, Frank. “Statement of Frank Meeink, Author and Activist.” U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Oversight and Reform, Subcommittee on Civil Rights and Civil Liberties, September 29, 2020. https://docs.house.gov/meetings/GO/GO02/20200929/111003/HHRG-116-GO02-Wstate-MeeinkF-20200929.pdf.

12. ‘Harold Covington’: One Stormfront reference

Disputes with Other White Nationalists and Movement Critiques

Covington’s advocacy for the Northwest Territorial Imperative emphasized mass migration of white nationalists to Idaho, Montana, Oregon, and Washington to achieve demographic dominance and enable armed secession, contrasting with prevailing white nationalist strategies of nationwide electoral engagement or localized community-building models such as H. Michael Barrett’s Pioneer Little Europe (PLE) concept, which sought to create ethnic enclaves anywhere without mass relocation. Critics, including figures like Greg Johnson of Counter-Currents Publishing, contended that this migration imperative embodied defeatism by effectively conceding the rest of the United States to demographic shifts and federal control, prioritizing retreat over a unified national resistance.[39] Such views framed Covington’s approach as abandoning kin in other regions, potentially weakening overall cohesion in favor of a geographically limited gamble vulnerable to encirclement or suppression.

In white nationalist online spaces, including Stormfront forums, Covington’s Northwest Front faced skepticism as overly quixotic or linked to repeated organizational failures, with discussions post-2018 highlighting its dissolution as evidence of strategic isolation rather than broader movement integration.[40] These critiques often portrayed the imperative as diverting energy from scalable activism, such as propaganda or legal challenges, into a high-risk concentration that alienated potential allies and reinforced perceptions of fringe extremism. Proponents of alternative paths, like those favoring PLE models, argued that dispersed efforts preserved nationwide presence and avoided the logistical burdens of uprooting families en masse.

Defenders of Covington’s territorial focus invoked empirical shortcomings of electoralism, noting that explicit white nationalist candidacies yielded no governing power despite high-profile bids; for instance, David Duke secured 31.8% in the 1991 Louisiana gubernatorial primary and 43.5% in the runoff but lost to Edwin Edwards, with subsequent decades showing no comparable statewide victories for similar platforms.[41] [42] They maintained that persistent failures in voter mobilization under hostile media and institutional barriers validated concentrating activists in a winnable redoubt, drawing on historical analogies like ethnic partitioning in post-colonial conflicts where demographic enclaves enabled leverage. This perspective positioned the imperative as pragmatic realism amid declining white majorities nationwide, though it risked entrenching divisions by dismissing hybrid strategies blending migration with parallel institution-building.

Public debates underscored these tensions, such as the 2011 exchange between Covington and Johnson, where the former hailed migration as innovative for fostering self-reliance and revolutionary potential, while detractors emphasized its cons in fracturing alliances and underestimating federal response capabilities.[39] Overall, Covington’s insistence on exclusivity—barring cooperation with non-migratory factions—exacerbated his ostracism, yet it spotlighted unresolved questions in white nationalist circles about whether incrementalism or bold relocation better addressed causal dynamics of power dilution.

Expanded stormfront.org reference in article:

40. Stormfront. “The demise of the Northwest Front.” Accessed November 22, 2025. https://www.stormfront.org/forum/t1319520.

Expanded other references in containing paragraphs:

39. Johnson, Greg. “Debate on the Northwest Imperative.” Counter-Currents, April 11, 2011. https://counter-currents.com/2011/04/debate-on-the-northwest-imperative.

41. Dave Leip’s Atlas of U.S. Elections. “1991 Gubernatorial General Election Results - Louisiana.” Accessed November 22, 2025. https://uselectionatlas.org/RESULTS/state.php?fips=22&year=1991&f=0&off=5.

42. Applebome, Peter. “Blacks and Affluent Whites Give Edwards Victory.” The New York Times, November 18, 1991. https://www.nytimes.com/1991/11/18/us/blacks-and-affluent-whites-give-edwards-victory.html

13. ‘James Wickstrom’: One Stormfront reference

Admirers’ Views on Patriotism and Resistance

Admirers within Posse Comitatus circles portrayed Wickstrom’s doctrinal emphasis on the group’s namesake as a principled revival of constitutional limits on federal authority, invoking the 1878 Posse Comitatus Act’s prohibition on military interference in civilian law enforcement to argue that county sheriffs held sovereign power as the highest legitimate government entity, thereby resisting centralized tyranny.[33][42] This interpretation positioned Wickstrom’s teachings as a defense of local self-governance against overreach, with supporters viewing the Posse’s structure—lacking formal hierarchy beyond the sheriff—as an embodiment of decentralized resistance rooted in American founding principles.[43]

In the context of the 1980s farm crisis, which saw over 200,000 U.S. farms foreclosed amid rising interest rates and commodity price drops, Wickstrom’s advocacy was lauded by adherents as vital support for debt-saddled families confronting what they deemed exploitative banker and IRS predation, including seminars on sovereign citizen tactics to challenge liens and auctions.[27][44] Followers credited his calls for armed preparedness to safeguard homesteads—such as urging farmers to “defend their families and land with their lives”—as heroic countermeasures to systemic economic warfare, fostering community networks that delayed or deterred repossessions in rural strongholds like Wisconsin and Kansas.[33][45]

Wickstrom’s Christian Identity sermons, delivered via radio broadcasts reaching thousands weekly in the 1970s and 1980s, were esteemed by devotees as uncompromised scriptural exegesis countering secular relativism, multiculturalism, and perceived dilutions of biblical covenant theology with identity politics.[4] Admirers in Identity-aligned patriot groups hailed his integration of faith with resistance as a moral bulwark, asserting that true patriotism demanded adherence to a divine racial and national order over humanistic universalism, thereby inspiring sustained opposition to cultural erosion through church-based mobilization.[46][47]

Expanded stormfront.org reference in the article:

47. Stormfront. “James P. Wickstrom 1942-2018.” Accessed November 22, 2025. https://www.stormfront.org/forum/t1283804.

Expanded other references in the containing paragraphs:

4. Southern Poverty Law Center. “James Wickstrom.” Accessed November 22, 2025. https://www.splcenter.org/resources/extremist-files/james-wickstrom.

27. Correll, Caleb. “Blood on the Plow: Extremist Group Activity During the 1980s Farm Crisis in Kansas.” University of Kansas Department of History, May 1, 2019. https://kuscholarworks.ku.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/e18f8567-0d3b-435d-adb3-f9c24e8bfddd/content.

33. Miller, John. “Politics of Hate in the USA, Part III: Posse Comitatus, Grassroots Rebellion, and Secret Societies.” e-flux Journal, no. 35 (May 2012):19. https://www.e-flux.com/journal/35/68410/politics-of-hate-in-the-usa-part-iii-posse-comitatus-grassroots-rebellion-and-secret-societies.

42. Weinberg, Leonard. “Posse Comitatus.” In Encyclopedia of the Great Plains, edited by David J. Wishart. University of Nebraska Lincoln. Accessed November 22, 2025. https://plainshumanities.unl.edu/encyclopedia/doc/egp.pd.045.html.

43. Snyder, Lee. “Born to Power: Influence in the Rhetoric of the Posse Comitatus.” In The Rhetoric of Social Intervention: An Introduction, edited by Susan K. Opt and Mark A. Gring. SAGE Publications, 2009. https://sk.sagepub.com/book/mono/the-rhetoric-of-social-intervention/chpt/born-power-influence-the-rhetoric-the-posse-comitatus.

44. Potok, Mark. “Timeline: Land Use and the ‘Patriots.’” Southern Poverty Law Center. Accessed November 22, 2025. https://www.splcenter.org/timeline-land-use-and-patriots

45. McLean, Jim. “Right-Wing Extremism Has Been Taking Root In Rural Kansas For Decades.” KCUR, July 5, 2021. https://kcur.org/news/2021-07-02/right-wing-extremism-has-been-taking-root-in-rural-kansas-for-decades

46. Abanes, Richard. “America’s Patriot Movement: Infiltrating the Church with a Gospel of Hate.” Christian Research Journal 19, no. 3 (Winter 1997). https://www.equip.org/articles/the-patriot-movement

14. ‘Matthew F. Collins’: One Stormfront reference

Accusations from Far-Right Circles

Collins has faced denunciations from far-right activists for his infiltration of the British National Party (BNP) and subsequent cooperation with anti-extremism organizations, portraying him as a betrayer of ideological comrades. Former BNP leader Nick Griffin labeled Collins “vermin” and a “state agent,” attributing the party’s internal disruptions and electoral setbacks partly to information Collins supplied to authorities and groups like Hope Not Hate, which exposed BNP operations and membership details.[43]

Such accusations often frame Collins’s transition from BNP activism to anti-fascism as opportunistic or coerced, with claims that he fabricated or exaggerated far-right threats to justify his paid role and public exposés. In far-right online discourse, including forums like Stormfront, he is derided as a “grass” (slang for police informant) whose actions facilitated arrests and organizational fractures, such as during BNP’s 2000s campaigns.[44] These criticisms dismiss his accounts in books like Hate: My Life in the British Far Right as self-serving narratives designed to discredit legitimate nationalist concerns while advancing state or leftist agendas.[3]

Griffin and other BNP remnants have further alleged that Collins’s intelligence work, including tips leading to membership vetting failures and media scandals, constituted sabotage funded by government entities, eroding trust within far-right networks and contributing to the BNP’s collapse by 2014.[45] Despite lacking independent verification of state payments beyond standard informant protections, these charges persist in far-right commentary as evidence of infiltration tactics undermining ethnic nationalist movements.

Expanded stormfront.org reference in the article:

44. Stormfront. “Combat 18.” Accessed November 22, 2025. https://www.stormfront.org/forum/t860216.

Expanded other references in the containing paragraphs:

3. Boycott, Rosie. “One man’s war against his demons.” The Guardian, March 9, 2002. https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2002/mar/10/politics.race.

43. Castle, Stephen. “Far-Right Party Strains to Hang On in Britain.” The New York Times, February 8, 2014. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/02/09/world/europe/far-right-british-national-party-strains-to-hang-on-in-britain.html.

45. Wigmore, Tim. “Nick Griffin resigns: Why has the BNP collapsed?” The New Statesman, May 22, 2014. https://www.newstatesman.com/politics/2014/05/why-has-bnp-collapsed.

15. ‘Matthew F. Hale’: One Stormfront reference

Supporters of Matthew F. Hale, particularly within white advocacy and separatist circles, have characterized him as a martyr whose legal battles exemplified viewpoint discrimination against advocates of racial preservation. They argue that his denial of a law license in 1999 by the Illinois Bar Committee and subsequent 2005 federal conviction for solicitation stemmed not from criminal intent but from institutional opposition to his ideological challenge to multiculturalism, framing his imprisonment as political persecution akin to treatment of dissidents.[77] This perspective posits Hale’s ordeals as catalyzing greater awareness of systemic biases against empirical discussions of racial demographics and group interests.

Hale’s leadership of the World Church of the Creator (WCOTC) is credited by admirers with pioneering models of organized, non-violent racial advocacy that emphasized “racial realism”—a recognition of biological and cultural differences among groups—through structured doctrine and widespread literature distribution. The WCOTC’s early adoption of online platforms for disseminating texts like The White Man’s Bible influenced subsequent movements’ digital strategies, including the alt-right’s deployment of memes and viral content to normalize critiques of immigration and demographic displacement without direct calls to violence.[19] This approach, they contend, contributed to broader societal shifts, as evidenced by polling data showing increased white identitarian sentiments amid projections of non-Hispanic whites declining from 67% of the U.S. population in 2005 to 47% by 2050, with surveys in the 2010s indicating nearly half of white working-class Americans perceiving cultural deterioration and a third believing insufficient protections for white interests.[78][79][80]

The persistence of the Creativity Movement, rebranded after trademark disputes following Hale’s 2005 incarceration, underscores his enduring impact, with adherents continuing to propagate WCOTC-derived teachings on immigration’s causal effects, such as economic competition and cultural erosion for native populations, while eschewing mainstream endorsements of violence in favor of separatist self-reliance. Supporters maintain this framework has sustained intellectual debates on group survival strategies, fostering successors who adapt Hale’s emphasis on white racial loyalty to contemporary contexts like opposition to mass migration policies.[81][10]

Expanded stormfront.org reference in the article:

77. Stormfront. “On Behalf of Political Prisoner Matt Hale.” Accessed November 22, 2025. https://www.stormfront.org/forum/t1360879.

Expanded other references in the containing paragraphs:

10. Southern Poverty Law Center. “Creativity Movement.” Accessed November 22, 2025. https://www.splcenter.org/resources/extremist-files/creativity-movement-0.

19. Michael, George. “The Church of the Creator Part II: Later Developments and the Sacralization of Race in Multicultural America.” Religion Compass 4, no. 9 (Sept. 2010):551-562. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-8171.2010.00235.x.

78. Passel, Jeffrey S., and D’Vera Cohn. “U.S. Population Projections: 2005-2050.” Pew Research Center, February 11, 2008. https://www.pewresearch.org/race-and-ethnicity/2008/02/11/us-population-projections-2005-2050-2.

79. Malik, Kenan. “The rise of white identity politics.” Prospect Magazine, July 13, 2020. https://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/essays/40417/the-rise-of-white-identity-politics.

80. Knowles, Eric D., and Linda R. Tropp. “The Rise of White Identity Politics.” The New Republic, October 28, 2016. https://newrepublic.com/article/138230/rise-white-identity-politics.

81. George, supra reference 19.